The Challenges of Estimating NTG, Part 1 - Baselines

One of the most difficult jobs that evaluators have is estimating attribution of savings to energy efficiency programs. Trying to put a numeric counterfactual value on a complex decision-making process is extremely challenging! I think it is this difficulty that makes it such an interesting topic to me. Let's dive in.

As stewards of ratepayer funds, program administrators should maximize the savings that can be attributed to the program. This is largely done by targeting customers who need the program’s intervention to make the energy efficiency improvement and by minimizing free-riders (those participants receiving incentives for measures they would have implemented anyway). At the same time, the presence of energy efficiency programs can result in indirect savings beyond its participants in the form of spillover and market effects.

What most[1] programs target is net savings, which the Uniform Methods Project (UMP) defines as “the difference in energy consumption with the program in place versus what consumption would have been without the program in place.” Stated as an equation:

Net Savings = Gross Savings[2] – Free-Ridership Savings + Spillover Savings + Market Effects Savings

Often, free-ridership, spillover, and market effects are expressed as a net-to-gross (NTG) ratio. Net savings can be calculated by multiplying gross savings by the NTG ratio.

While there are methods to determine net savings directly (e.g., through quasi-experimental designs or market sales data analyses), evaluators often use surveys to collect information to estimate NTG. This approach is cost-effective and transparent but has many potential issues. Again, attempting to measure a complex decision-making process is really hard!

Evaluation experts in jurisdictions throughout the country have been tackling survey-based NTG issues for decades in an effort to improve the accuracy of NTG measurements. Through the sharing of best practices, evaluators have been able to incrementally improve NTG methodology although important work remains. Some concerns these groups are addressing include (but are definitely not limited to):

- The design of questions (e.g., are questions phrased in a way that participants understand the concept being measured, are they able to answer these questions, and are the appropriate scales or response options included?)

- The algorithm used to translate survey responses into estimates of free-ridership and spillover (e.g., which questions should be included and how should they be weighted when combined?)

- How best to include the influence of the program affecting but not visible to the participant (e.g., program-sponsored contractor training)

Baseline Issues

One issue I would like to highlight is the baselines used in NTG research. To calculate net savings, evaluators must first determine the appropriate baseline (i.e., the counterfactual scenario) to determine what could happen in the absence of the program.

There are three critical questions:

- Is the program using the correct baseline?

- Does the program baseline align with participants’ typical counterfactual scenario?

- Is the survey correctly framing the baseline to the respondent?

If the NTG research is not well aligned with how the program measures savings and if respondents do not understand the survey questions, there is potential that the NTG ratio will not reasonably reflect the impact of the program and, by extension, its net savings.

In many cases, the choice between efficient and inefficient equipment is clear and easily articulated to NTG survey respondents. In other cases, the counterfactual scenario is much more complex. For example, in smaller commercial new construction projects, the baseline building (according to ASHRAE Standard 90.1 Appendix G) is to be modeled with single-zone HVAC units to condition spaces rather than a central system. If the participating building installs a high-efficiency chiller, it is compared to the low-efficiency unitary equipment and not a lower efficiency chiller, which is likely not a realistic representation of what would happen in the absence of the program.

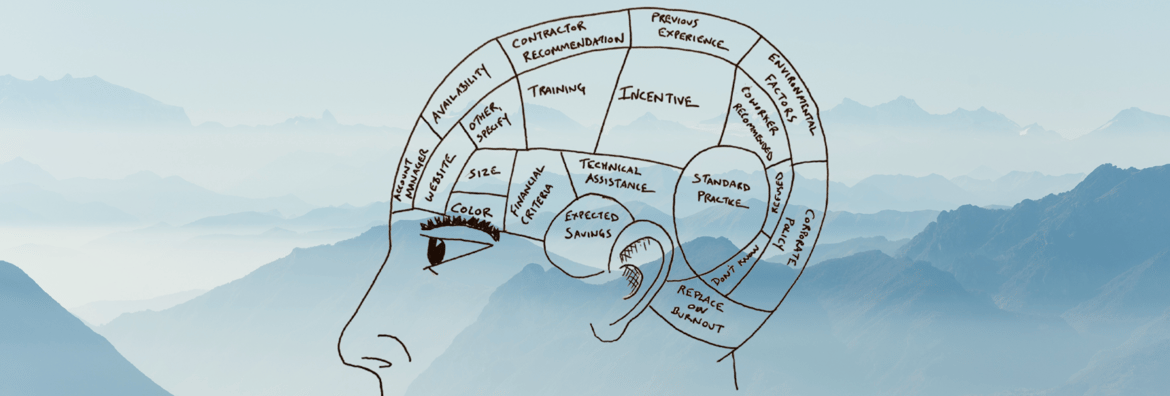

To estimate the program’s attribution, evaluators typically include questions that ask about the influence of various program elements (e.g., incentive, training, technical assistance, etc.) on the decision to install energy-efficient equipment instead of the baseline and the likelihood of installing the same energy-efficient equipment if the program had not been available. In order to get as accurate an estimate as possible, evaluators need to frame questions so that they correspond with how the program calculates savings and with how the respondent makes the decision.

.png?width=975&name=edafb050-d244-468c-8654-60b33764cf19(2).png)

This figure illustrates some of these NTG baseline issues for a commercial new construction program.

- Equipment Type: As described above, although the program measures savings by comparing the energy usage of the installed high-efficiency chiller to the usage of unitary systems, the respondent’s actual choice may have been between chillers of different efficiencies.[3]

- Efficiency Level: The program measures savings by comparing the installed equipment and the code minimum. However, the program’s baseline (code) may not align with the market baseline (i.e., what the competition is installing). Additionally, what the building designer may have originally planned prior to the program’s intervention may be different than the market baseline. This means that the respondent may not attribute much of the savings the program is claiming (i.e., the difference between code and market baseline or between code and what was originally planned) to the program.[4] Alternatively, if the respondent is only considering the program’s impact on their decision to move from their planned equipment to what they installed, the net savings may be overstated if that ratio is applied to the program’s definition of gross savings.

Attempting to quantify the impact of programs on participants’ decision-making process is difficult and will never be perfect. This is especially true for programs with complex counterfactual scenarios. Evaluators need to continue to review NTG methodologies and incrementally improve them over time. Methodologies should also be flexible enough to adapt to the wide range of programs offered, as no one size will fit all. Programs and evaluators should also work together to ensure that the baselines used in both the gross and net savings as well as the counterfactual scenario used in the NTG surveys all align in order to best estimate the impact of the program…at least as best we can.

[1] But not all!

[2] The UMP defines gross savings as “the difference in energy consumption with the energy efficiency measures promoted by the program in place versus what consumption would have been without those measures in place.

[3] In another scenario, if the participant installed a ground source heat pump, the code baseline would be a low efficiency air source heat pump but the actual counterfactual could be a gas heating system.

[4] This only considers the impact of free-ridership on NTG. Conceivably, the program could claim some portion of the savings between the baseline efficiency and the planned equipment through spillover or market effects.

-1.png)