Decoding Code Compliance, Part 2

In Part 1, we covered what energy code programs do and different ways of measuring code compliance. In this part, we will examine the steps needed to estimate program savings.

Code adoption and compliance change over time. To estimate savings, we must consider the counterfactual of what would have happened if the program did not exist. When would a code have been adopted and how would building practices have changed over time? These are not easy questions, but let’s dig in.

If Only It Was So Easy

Recently I was looking through the Rhode Island TRM and chuckled when I found this description of the state’s Codes and Standards program:

The baseline description sounds so simple, right? To calculate savings, you only need to compare the current adoption of codes to “the un-influenced adoption curve.” I have nothing against Rhode Island or the program, but that one sentence really highlights how difficult it is to estimate savings from energy codes programs.

In order to claim savings, the program needs to have a methodology to:

- Establish a baseline (i.e., estimate compliance without the program)

- Determine the change in compliance over time

- Quantify the change in energy savings

- Estimate attribution to program

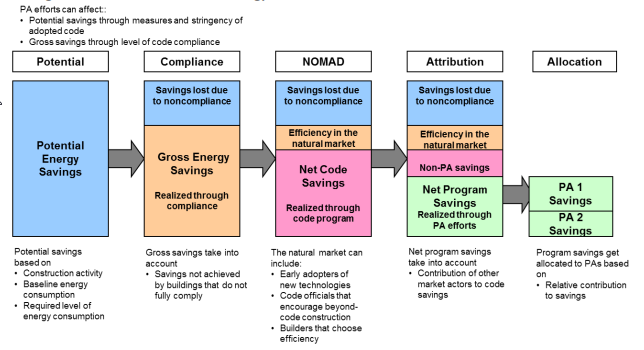

The figure below illustrates these steps in more detail.

Figure 1. Model of Energy Code Evaluation and Attribution to Utilities/PAs (NEEP 2013)

Source: NEEP

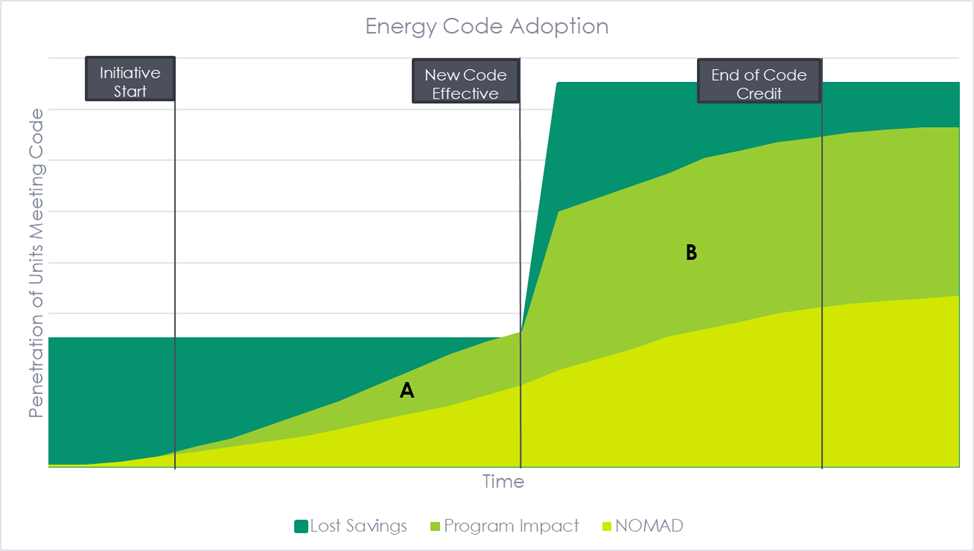

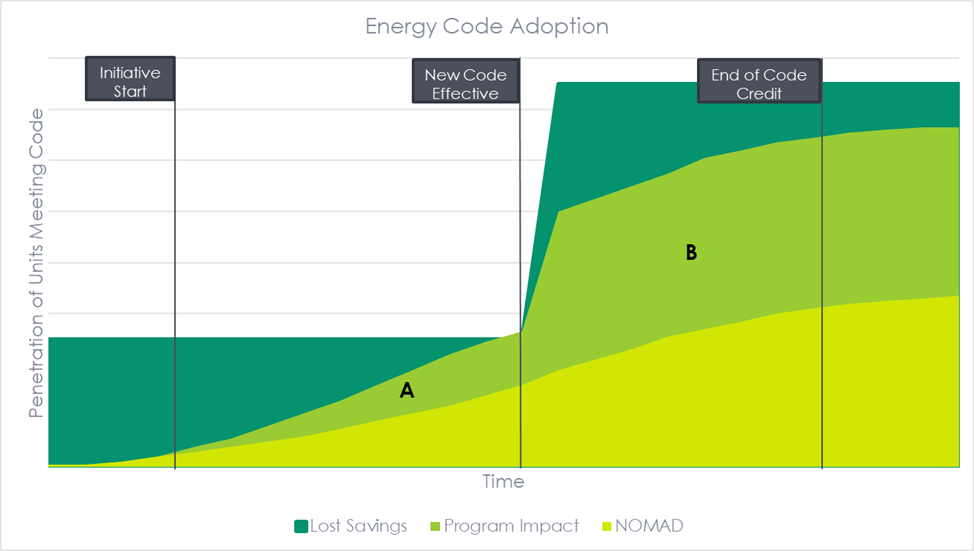

In addition to helping to increase code compliance, some energy codes programs also advocate for higher levels of efficiency in energy codes. In the figure below, the program’s activities increase the total market adoption of energy-efficient equipment that meets code beyond the naturally occurring market adoption (NOMAD). The program’s impact could come in two parts. First, the program could claim some credit (area A) for its influence on the code’s incorporation of higher levels of efficiency. It then could claim credit (area B) for increasing compliance in its jurisdiction after the new code has been adopted. Note that at some point, the program would not be able to take credit for its influence on the latest code iteration, but could potentially start to influence the next iteration.

Figure 2. Illustration of Energy Code Adoption

Based on a figure from the Illinois TRM

Note that the y-axis of the figure above shows the penetration of units meeting code as a simplification. What really matters is the reduction in energy use and this can often be done with a variety of equipment types or configurations.

Establishing a Baseline

The first step for a program to claim savings is to establish a baseline of what the compliance would be without the program. The difference between the baseline and code is the potential savings.

If there is currently no energy code program, then this might be as simple as determining the current level of compliance. However, there may be some code-related market effects from other incentive programs (e.g., new construction programs) that need to be taken into account.

In the previous post, we discussed code compliance at a high level, but when estimating savings, there are many factors that need to be considered when studying code compliance. First, what information is being used to assess code compliance? Is it a code compliance study using site visits and/or building plan reviews? Is it an assessment of industry-standard practices using expert interviews or a Delphi panel (and who are those experts)? Or is it a review of market data or shipments from manufacturers? Second, what is the sample size? How many buildings are needed to provide results at the desired confidence/precision level? That has huge cost implications. Third, what is being analyzed – is it building permits or actual construction/installations? What is actually implemented is often different than what is planned and even if they are the same, the equipment may not be constructed or installed correctly. These questions only scratch the surface.

Determining the baseline in a jurisdiction where energy codes programs already exist is more complicated. In these cases, we much account for the effect of the program’s past interventions.

Determine Change in Compliance Over Time

Next, the program needs to measure the change in compliance over time. On the surface, this step is easy because it just represents an additional snapshot in time to understand what has changed from the initial estimate described above. One potential issue is NOMAD and/or impacts from other incentive programs may result in a baseline above code. Estimates of compliance need to be able to account for over-compliance as well as under-compliance.

Quantify Changes in Energy Savings

As discussed in Part 1, programs and evaluators can convert energy code compliance into energy savings by using the PNNL tool or using an energy simulation model. Complicating things is that building energy codes apply to equipment and systems that interact and compliance will be different for each component, resulting in cascading effects.

Estimate Attribution to Program

The final step in claiming savings from energy code programs is to determine how much of the energy savings are attributable to the program. This is the most difficult step in the process.

First, we must estimate how much of the savings from code compliance is due to NOMAD, then how much is due to program intervention versus other factors, and then, finally, which program administrator gets the credit.

There are several challenges to work through. First, code adoption and compliance change over time. For example, some states adopt a new code every other cycle, and often there is a delay from when a code is introduced to when it goes into effect in a given jurisdiction. Second, energy code programs change over time as well and their impact is not constant. Third, a program cannot claim savings from its intervention forever; there must be some limit on the duration of the savings claim. Finally, there are many parties working to improve energy codes, and code compliance and credit must be appropriately shared. Statewide frameworks are often needed to allow utilities to claim savings for their efforts.

How do we measure program attribution? Most often it is through interviews with industry experts or a Delphi panel. Estimating a counterfactual (i.e., how would equipment and building efficiencies have changed in absence of programs?) is very difficult to begin with and energy code programs target the broad market rather than specific purchasers of energy-efficient equipment. This means that people with industry-level rather than project-level observations can most likely provide valuable insight. Still, this process is far from perfect and attempts to refine the process continue.